“I imagine good teaching as a circle of earnest people sitting down to ask each other meaningful questions. I don’t see it as the handing down of answers. So much of what passes for teaching is merely a pointing out of what items to want.” Alice Walker

“The strongest human instinct is to impart information, the second strongest is to resist it.” Kenneth Graham

Introduction and Purpose

Following our interview with long-time Japanese headgear collector, John Egger, I thought that it would be interesting to re-visit a subject that has been discussed for quite some time at military antiques shows and on a few military history forums in the recent past: Japanese Type 90 Camouflage and/or Non-Standard Painted Helmets. The valid existence of Japanese helmets, altered with paint, from the World War Two period used to be accepted as a given: a number have been seen over the years, with collectors adding them to their collections sometimes, via dealer sales, or by finding them at flea markets and garage sales. Additionally, in the early days, camo helmets were frequently obtained directly from the veterans themselves. However, more recently with research being done into Japanese wartime regulations, doubt has been cast onto the authenticity of helmet examples found, painted in patterns or with colors other than the standard shades.

The purpose of this article is to dissect some of the more popular arguments made against Japanese non-standard or camouflage painted helmets and to ask: How likely is it that the Japanese military in World War Two never painted their Type 90 helmets in non-standard shades of paint? If there is no written account as to why the helmet was painted a different color shade, does it make the helmet a fake? The following are some of the questions that will be reviewed in order to let you decide for yourself:

1-Were veteran-acquired, non-regulation painted helmets all fakes or as some have said, creations with post-war additions and alterations?

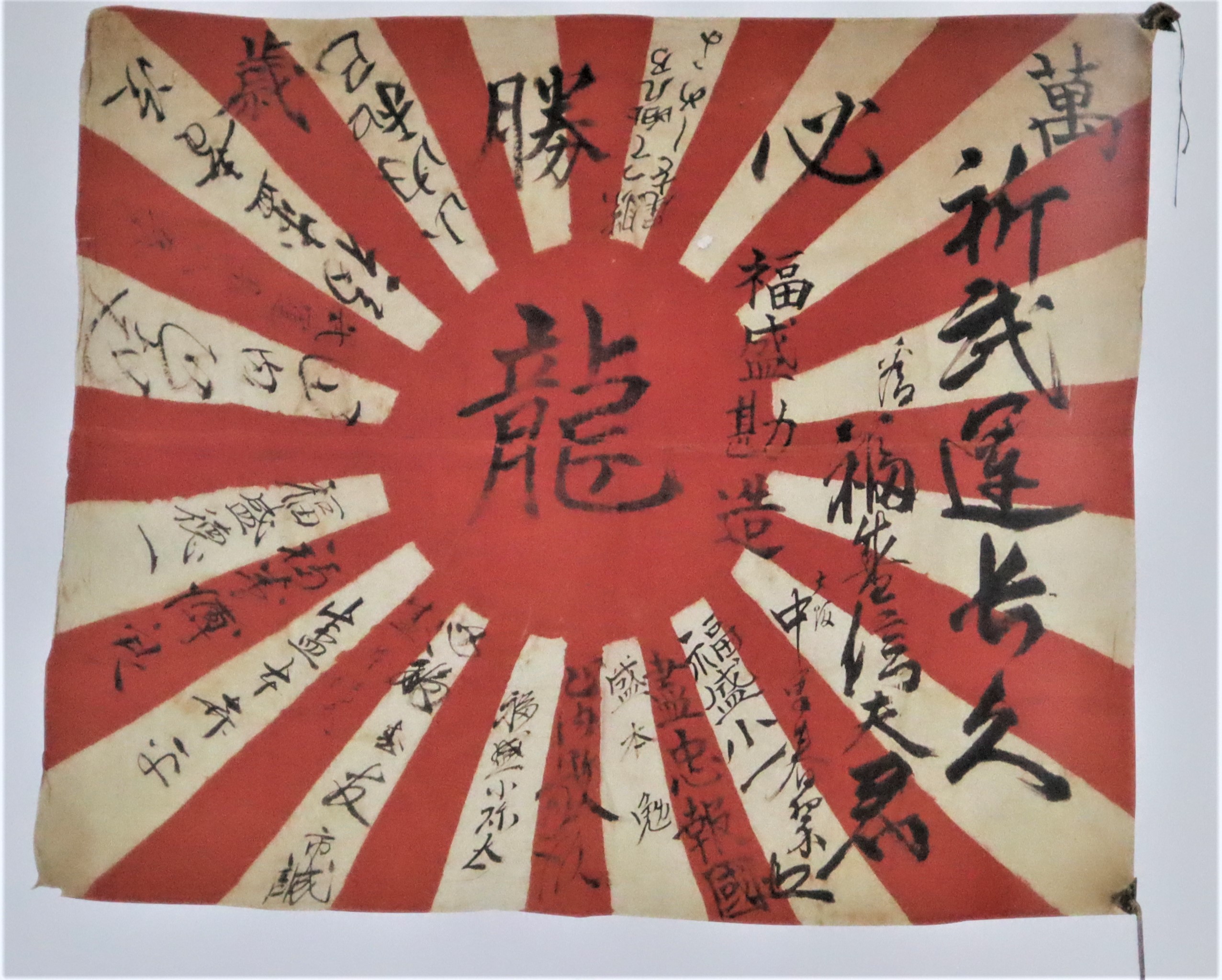

2- The United States Navy Seabee’s and the making of fake good luck signed flags: Were the Navy’s Seabee’s too busy operating lucrative fake flag and bogus war souvenir operations, (those operations are also supposed to have included the “doctoring” of helmets) than to fight and help to win the war?

3- Did the Japanese strictly follow the uniform and weapons regulations at war’s end, in the same manner that they did in the beginning of the early China War or did they alter them as needed? Might there be additional explanations for camouflage painted helmets?

4- When did the Type 90 helmet come on the scene? What were the regulations for painting them during the war?

5- Did the prosecution of the war make it difficult for the Japanese military to resupply its forces with essential and non-essential items over time? Could shortages have led to helmets that were painted with likely available or combined paint stocks? Could helmets have been painted in small quantities of non-regulation colors based upon immediate necessities or targeted uses?

6- Do we know approximately how many Japanese helmets were produced during the war? Is it practical to think that none of these were ever painted in non-regulations shades or were there exceptions?

7- How does the material culture (visa vie the archaeology) speak to us? How does it affect what we think we know?

Allied veterans returning home from the Pacific battlefields of World War Two, brought with them many different kinds of Japanese war souvenirs. Practically anything that sported an exotic Japanese kanji character was fair game; even discarded empty boxes found their way into America’s post-war attics, basements and garages. While nearly everything imaginable seemed to make it home to the United States via its returning servicemen and women, three of the most popular items brought back by military personnel were: samurai swords, good luck signed flags and army or navy steel helmets. The vast numbers of each, still seen in the United States today, nearly 75 years after the war, indicates that this is true.

While not as frequent today as in years past, verbal exchanges with United States World War Two veterans was an everyday occurrence to many of the “Baby Boomer” generation (1946-1964). Family and neighborhood gatherings, holiday celebrations and chance encounters, often led to some kind of dialogue between these veterans and kids or young adults. The younger generation, primarily of the 1950’s, ‘60’s, and 70’s, grew up on a steady diet of World War Two themed films starring John Wayne and similar Hollywood notables. Movies such as: The Flying Leathernecks (1951), The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and newer classics like the famous Pearl Harbor attack movie, Tora, Tora, Tora (1970) and later, The Big Red One (1980), fueled the imaginations of people who desired to know, as George C. Scott’s, Patton (1970) once said in his famous monolog about an aging U. S. veteran’s conversation with his child, “What did you do in the great World War Two?”

Later, television programs such as: Victory at Sea (1952-1953), 12 O’clock High (1964-1967), and Combat (1962-1967) ingrained into the psyches of Americans, the harrowing deeds that so many of their fathers, uncles and grandfathers had lived out during the war. Succinctly stated: America’s Greatest Generation of veterans, became the heroes for America’s later generations. Their war souvenirs or bring-backs were the, “not so silent proof”, that the history was real. The truth is that hundreds of collectors of war time militaria had similar experiences.

Helmets, were frequently brought out by veterans and shown to their young charges, while the story of how the veteran acquired it were discussed. Often, these pieces of history were given away afterward to those who appreciated hearing the oral histories.

One of America’s most decorated soldiers of World War Two, from the ETO, Audie Murphy, was once asked about whatever became of his military awards and decorations? Murphy was reported to have said that after recounting his exploits with the neighbor kids, he gave away his Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, 2 Silver Star medals and the rest, to the kids to wear while they ran around playing war games. I would like to think that some of those early collectors grew up to become any number of things: today’s museum directors, teachers, writers, military historians, anthropologists, textile conservators, veteran’s advocates and of course, militaria antiques collectors.

My own father was a veteran pilot of World War Two. I had a number of uncles and friends who fought their way across the battlefields of the Pacific and Europe. I first began to collect militaria with items that were given to me by these men and later on, acquisitions from garage sales and flea markets. These veterans had no reason to alter their battlefield pick-up’s that included helmets, items that often remained packed away in their duffel bags since the war’s end. In that regard, common first-hand exchanges between helmet buyers and veteran sellers are often remembered quite vividly and frequently went something like this: Buyer to Veteran- “You don’t often see Japanese helmets painted in this color. Did you paint this helmet white/black/green, etc. yourself?” Veteran Seller to Buyer– “Why the hell would I have painted this helmet any color? That’s the color(s) it was when I picked it up on the ground at Saipan, Guam, Okinawa, etc., following the battle.” (*Note: I am not talking here about the “art” helmets that are sometimes encountered with designs or battle place names and dates recorded on them during or post-war. See below)

The U.S. Navy SeaBee’s as fakers of war souvenirs

The castigation of United States Navy Seabee’s for faking or somehow creating fantasy improvements to nearly every captured weapon or piece of equipment including helmets, on an immeasurable scale, has for the sake of some, been profitably linked into an easy catch-all in an attempt to explain a narrow view of the non-standard helmet paint schemes encountered by collectors. The undeniable fact is that there were those in the United States Navy, known to have faked Japanese signed flags, some indicate in volumes. Yet those who spend time, “down on the streets” within the hobby and who personally handle these and other items frequently, wonder aloud at how, after studying the extant artifacts and accompanying comments, the Allies in the Pacific ever had the time to win the war, with so many men apparently working around the clock to fake the already ubiquitous good luck flag!

Photographic evidence too, albeit primarily in vintage black and white images, does seem to indicate that Japanese helmets did not always follow what we have come to recognize as the standard khaki color paint scheme, named “dead grass” by the Japanese. Helmets camouflaged with white covers or those painted outright in white paint, have been easier to identify from vintage photographs. That being said, there are photographs in the hands of collectors that indicate that there were a variety of helmets and even helmet insignia (painted or not) in lighter, medium or darker shades of paint, some of which may all be seen in combinations, in a single image.

Today, vintage helmets are commonly encountered by collectors with lighter or darker single bands of paint running around their rims; the scratched metal surfaces having been touched-up, following shipment. If the paint formulas were regulated and standard, then why did these touch-up’s stand out so differently on these often recently serviced helmets? In the end, the lighter or darker striped helmets should qualify as camouflage anyway since the net effect of the stripe addition is to break up the visual impression of the helmet, in effect deceiving the eye (this is one definition of “camouflage”).

History of the Type 90 Helmet

The Japanese officially adopted the Type 90 helmet in 1930 but it was not until mid-summer of 1932 that the army eventually abandoned the older “Cherry Blossom” style helmet for its front-line personnel. In that same year, Japanese army helmets went from being classified as a weapon, to an item of clothing. Additionally, it received a new name, tetsu bo or “iron hat”. (*Note: In martial arts, this same term is frequently used to describe a weapon, known as an iron quarterstaff.)

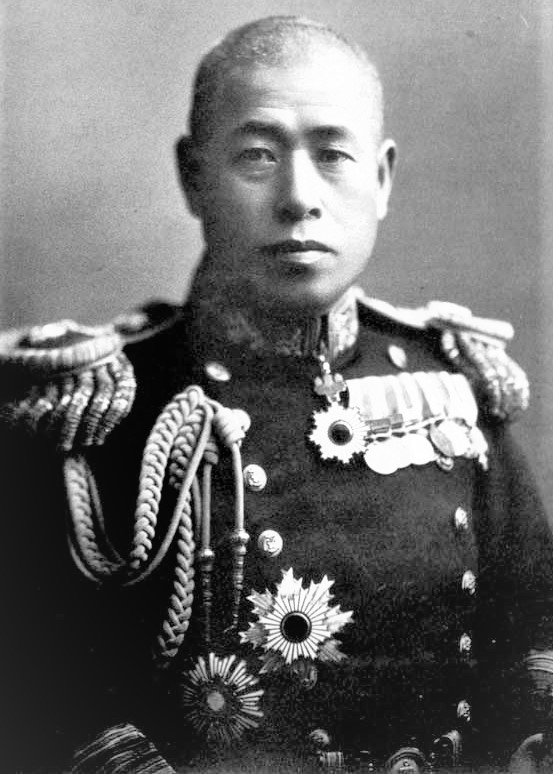

The Japanese navy, on the other hand, continued to maintain that helmets were weapons and stuck to the older term, kabuto. In the Japanese language, kabuto is a noun and not a type description and for purposes today, can refer to any combat helmet or personal armor. While the army was upgrading equipment, the Japanese navy continued to use the “Cherry Blossom” style helmet as a primary piece of its battle gear, only briefly requisitioning a couple of hundred of the Type 90’s in 1933. In 1936, Vice Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto of later Pearl Harbor fame, was made Vice Minister of the Navy. The following year, as the events surrounding the Marco Polo Bridge Incident escalated, the Admiral officially requisitioned 4000 of the army’s Type 90 helmets for use by his sailors.

They just never would have done that, except…

A key aspect of the anti-camouflage paint argument, is a cultural one: it follows that the Japanese soldier or sailor, philosophically and military-legally, would not have taken it upon himself to alter his uniform gear or weapons in any way, for fear that by doing something as blatant, for example, as changing the standard color of the helmet from its sanctioned khaki-type shade to anything else, would have invoked severe punishment. It is true that Japanese military culture admonished that individuality was not to be tolerated. The equipment, first and foremost belonged to the Japanese Emperor and no one would have dared to disfigure “his property” in any manner, knowing that there could be retribution by one’s superiors for such acts. In a cross-linkage, stories of especially severe punishment for infractions with regard to one’s rifle have been made to further show that no one would be foolish enough to mess with one’s helmet or any other piece of uniform/weapon either. In common sense terms today, punishment for neglecting one’s rifle still has to do with the fact that such negligence, particularly during a war, could affect not only the lives of oneself but also, those of the entire unit. Nearly every military in the world, not just the Japanese, have similar rules with regard to this subject.

While official regulations specified that individuals were not to alter their clothing or helmets, it appears from some sources, that this did not apply to groups of men that obtained permission from their superiors for specific reasons. Some writers have stipulated that any changes that were broadly made, were done so on a limited basis and remained entirely with that group. It was conveniently spelled out, that any alterations would necessarily have been recorded somewhere in order to prevent punishment to these men, later on. This logic therefore renders almost any helmet found not painted in regulation shades as somehow suspect. More so, it has the further convenient effect of deflecting the fact that differently painted helmets exist and are in multiple hands. I would chance that if the changes to the paint were made on a small scale, for whatever reason, i.e. limited function or usage, no regulation paint available, changes due to desperation in battle where there were little or no survivors to the action, etc., then it makes sense that there would be no record of the changes either, only the material culture, the helmets themselves, exist.

It appears that the door is now open to the fact that some Japanese uniforms and equipment may have been altered in specific instances. As a nod to this fact, writers have even said that there were hardly any non-regulation modifications performed on a Japanese soldier’s equipment items; this statement, of course, by its use of the qualifying terms, lends itself to the fact that modifications probably did exist.

Returning to helmets, the Japanese army’s regulations on camouflage say that the helmet color was not to be changed [from the standard shade], although practical exceptions were allowed in instances such as snow, where helmets could be painted white. That fact and the record from the material culture (stuff brought back), indicates that indeed, white painted helmets have found their way into the hands of veterans. This makes common sense as many of Japan’s troops fought in countries where snow covered the ground for months on end.

Japanese military ordinances early on, regulated the care and maintenance of one’s equipment, including the helmet. Documents from 1932 specified that the repair of all damaged helmets would become the responsibility of each unit. Units stationed in the field were supposed to be supplied with all of the parts needed in order to maintain the field readiness of that piece of equipment. The parts needed to perform this function included: helmet liners, liner pouches and their pad inserts, rivets, rings, tie strings, insignia and paint. Regulations further stipulated that all field units were to perform these repairs themselves.

Resupplying the Japanese held island bases was a nightmare

The ability to thoroughly follow uniform and helmet maintenance regulations, especially during the early years of the War when supplies were, across the board, more easily available, seems plausible. Equally as reasonable, it seems sensible to ask: What was the likelihood that this would continue everywhere, one hundred percent of the time, as the war progressed and Japan faced extreme shortages? It really depends upon how badly Japanese troops in the field faced shortages. The truth is that even after the Imperial naval forces laid a blistering defeat upon the American navy at Pearl Harbor, cracks in the armor of Japan’s logistical war plans began to surface relatively quickly. To see just badly conditions were for the Japanese armed forces, let us take a look at the following article by the U.S. Naval Institute:

“Aggressive army doctrine translated into fast-moving, infantry-centered operations that overran British Malaya and drove Allied forces from Burma by May 1942. Simultaneously the army conquered the Netherlands East Indies and the Philippines and moved small numbers of troops into the Bismarck’s, Papua New Guinea, the Mariana’s, and the Solomon’s. Japan’s powerful navy, the strongest in the world after the Pearl Harbor attack, swept the seas of Allied warships, secured the army’s line of communication to the southern regions, and provided air support as ground units fanned out across the Pacific. In exchange, the navy demanded ground troops to defend its far-flung conquests, and the unforeseen requirements overextended the army. Then Vice Chief of Staff Lieutenant General Tsukada Osamu likened the scattering of small army detachments throughout the Pacific to “sowing salt in the sea.” Japan’s sensational string of victories during the initial stage of the war also masked fatal structural and institutional weakness in the military’s command and control system. Interservice strategic and operational planning was almost nonexistent, and joint operations were ad hoc reactions to events. After the U.S Marine Corps landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942, for example, the navy demanded army reinforcements to retake the island, but army general staff officers in Tokyo did not know where Guadalcanal was, much less that the navy had established a small base there.”

As the days passed, soldiers and sailors who made up the core of Japan’s far flung island empire, faced an escalating paucity of essential materiel. The negative progression of the war, would necessarily have made shortages of less important items like uniform colored paint for helmets, possible. Simply put, Japanese units at times found themselves unable to be refitted or resupplied with even the basic needs of replacement personnel, adequate food, uniforms, rifles and miscellaneous parts for equipment repair. Added to this was the harsh fact that humid and damp living conditions throughout the Pacific islands brought about continuous rotting and rusting of all kinds of military goods. Steel helmets were prone to corrosion and according to regulations, needed to be serviced. What could be done, then, to maintain one’s equipment, including a rusty helmet?

It makes sense that in some locations, over time, keeping helmets all looking homogeneous in color would become a near impossible task. Japanese soldiers and sailors stationed, on many of the bypassed or poorly supplied islands, would have done the best that they could with the limited resources that they had at their disposal. When exact matches were not available, helmets were undoubtedly coated with paint combinations that in instances, looked similar to but not necessarily the exact same, as the “dead grass” color.

The U.S. Naval Institute succinctly summarizes it this way:

“Overstretched across the Pacific’s vastness, the army was vulnerable to Allied air and submarine interdiction campaigns. Thousands of Japanese combat troops and tens of thousands of tons of equipment never reached their destinations.”

In that regard, the United States Navy laid down its utility buckets, bedsheets, paintbrushes and spray paint guns and methodically sank or systematically prevented Japanese naval vessels from ferrying sufficient necessities to its island strongholds.

Consider again the gravity of the situation across Japan’s holdings: In yet one more well-known example, during the spring of 1944, U. S. naval forces, having broken the Japanese secret code, a la, “Ultra”, homed in on the Japanese Take Ichi Convoy (“Bamboo No. One Convoy”), sailing from Shanghai, China and bound for stops in Mindanao, Philippines and Western New Guinea. Under the command of Rear Admiral Sadamichi Kajioka, the convoy’s main objective was to safely deliver men and supplies of the army’s 32nd and 35th Division’s. On two occasions: April 26 and May 6, U.S. submarines met and sank 4 transports, killing 4,000 Japanese troops. The remaining ships in the convoy were diverted and the troops and supplies failed to reach their destinations.

In the months preceding the invasion of Saipan, Japanese shipping losses exceeded 200,000 tons of reinforcements and materiel destined for the Central Pacific. It is estimated that at least 3,500 men bound for Saipan never reached their final port. At the same time, the Japanese army’s vital, supply and transport barge system (estimates suggest that there were as many as 6000 transport barges in use), had been under constant daytime attack and were being forced to travel at night; many were knocked out by Allied naval and air assets. By early 1945, American submarines had gained such extensive control over the shipping lanes and the threat of loss was so likely, that the Japanese Headquarters Staff in Tokyo turned down the Okinawa garrison’s plea for additional troops, realizing that their loss would be catastrophic; those troops were on their own.

How many Type 90 Helmets did the Japanese manufacture?

An important question in this discussion needs to be asked: “How many Japanese helmets were actually produced during the War?” A calculation of production numbers beginning from 1931 thru 1945, shows that approximately 6 million units (some think that the numbers may have been as high as 8 million units), were manufactured. Once the United States entered the War, its military would have been in contact with Japanese military personnel predominantly wearing the Type 90 steel helmet. This, in fact, is the example historically seen in most of the bring backs by veterans. Different helmets would likely have been encountered from time to time too and this is borne out as some veterans reported that they took “Cherry Blossom” helmets off of Okinawa following the fight there; some of those pieces of headgear were purchased from those very veterans. Other types of helmets have undoubtedly been recovered from the Pacific battlefields as well.

Now, I would like to change focus away from the supply and shortages of war that affected helmets and paint and consider some numbers. Assuming that 6 million Japanese helmets were manufactured, how likely could it be that any were camouflage painted by the Japanese, worn into the field and brought back as war souvenirs by the Allies? Some sources have indicated earlier that hardly any helmets but the standard colored ones, would have existed or been tolerated. Again, since “hardly any” indicates that “some did” what sort of numbers are we discussing? The answer to that is honestly unclear.

“Hardly any” Japanese helmets were likely to have been painted in non-regulation shades and patterns. So, how many might that have been?

If you take the figure of 6 million helmets produced and decide that not many of that number could have been camouflaged due to: cultural indoctrination, severe regulations as stipulated earlier, and materiel shortages, while at the same time consider that some changes did happen or were allowed due to sanctioned and documented exceptions, noted changes in the field, etc., then what kind of a number should we consider may have been camo painted? If perhaps ten percent were not painted in regulation paint shades over the course of the years, that number is a whopping 600,000 units. Practically speaking, that number of potential helmets painted in camo-type configurations and colors is beyond believable. It’s just too high for what we see in the hands of collectors and museums along with taking into account probable units thrown away or destroyed post-war. What if we take a much smaller, more conservative number like one percent of 6 million; what does that tell us? The answer is that it equals roughly 60,000 helmets that might have been camouflage painted or covered in non-standard shades at one time during the war. To put that figure into perspective, one percent of 6 million nearly equals the same number of Japanese troops (59,336 men), that were stationed on Guadalcanal, Tarawa and Saipan combined, at the time of the American invasions of those islands; that would still be a lot of helmets.

If I wanted to further beg the question; What if we took a ridiculously small number such as one-tenth of one percent of 6 million? That would indicate that approximately 6,000 helmet units could have been camouflage painted at some point during the war and ended up as the “hardly any” examples in people’s collections today.

The value of material culture and interpreting what the helmets (or anything else for that matter) want to tell us. And, Conclusion

Taking into account helmets-in-hand and situational realities, we have demonstrated that there is the likelihood that some Japanese World War Two helmets were not painted solely in their regulation shades and some in fact, appear to have been altered by Japanese troops in the field. Furthermore, the fact that we do not know what each of those helmets was used for, i.e. black, multi-colored or striped examples or that there is no officially documented Japanese story as to their creation, does not negate their authenticity as legitimate, vintage Japanese World War Two era relics. Supporting records may have been lost or destroyed, if they ever existed and eye witnesses to the events may have been killed or died over the ensuing years. If any observers were found, it is likely that recording the fact that they had covered their helmets in off-shades of paint, was unimportant in comparison to the life or death events that they faced.

Militaria collectors, museums, amateur researchers and academic historians from around the world all have important roles to play in helping our community at large better understand the kinds of uniforms, weapons, and accoutrements that the Japanese forces of the World War Two era carried into battle. One segment trying to stand without the support of the others is like trying to walk on one-leg; there is not going to be much progress forward.

One purpose behind anthropological research is to verify if what we think we know is so. If things prove different, we may be led to make new assumptions. Source and document research may provide important baseline understanding or they may add further details to our comprehension of any topic. At the same time, they may lead us into a new discussion about a topic that seemed buttoned up. Any of this, however, is incomplete at best without the stuff to study as well. The search for artifacts is the reason that we send archaeologists into the field. If we already knew what was so by reading the book, we would not need the items themselves, they should only corroborate what we studied between the bindings. The material culture provides an important key that should not be ignored. We hope that by examining the relics that people used, we may begin to more fully grasp the nuances of the subject that we have begun to study, even if they complicate things. The artifacts give us a broader, more complete truth into the lives of the people that actually lived the history. In some instances, our understanding is confirmed but sometimes, for example, the helmets that we study, suggest something a bit different.

I would like to again see collectors begin to share their “other than standard” Japanese painted helmets with the rest of the hobby. Within that community, everyone should have the ability to discuss the possibilities behind such examples, rather than simply hear that they, “never would have done that”. Well, hardly ever……

Michael Bortner

September 12, 2019

A Sampling of Camouflage Painted Japanese Type 90 Steel Helmets

Bibliography

Blair, Clay. Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan. Annapolis: MD. Naval Institute Press. 2001.

Bortner, Michael A. Imperial Japanese Good Luck Flags and One-Thousand Stitch Belts. Atglen: PA. Schiffer Publishing. 2008.

Forbes, Peter. Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. New Haven: CT. Yale University Press. 2009.

Jowell, Philip. Japanese Army 1931-45 (Volume 1 1931-42). Oxford: UK. Osprey Publishing. 2002.

Morison, Samuel E. History of the United States Naval Operations in World War Two: New Guinea and the Marianas March 1944-August 1944, vol. 8. Edison: Castle Books. 2001.

Nakanishi, Ritta. Japanese Military Uniforms: 1930-1945. Tokyo: Japan. Dai Nippon Kaiga Publishing Co., Ltd. 1991.

Smith, Michael. The Emperor’s Codes: The Breaking of Japan’s Secret Ciphers. London: UK. Penguin Publishing Group. 2002

Wise, James E., Baron, Scott. Soldiers Lost at Sea: A Chronicle of Troopship Disasters. Annapolis: MD. Naval Institute Press. 2003.

Drea, Edward J. “The Seldom-Seen Enemy”. The U.S. Naval Institute. Naval History Magazine. April 2010, vol. 24, no.2.

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2010/april/seldom-seen-enemy

(The Japanese soldier gained a World War II reputation for fight-to-the-death tenacity even though Japan’s imperial army was overstretched and plagued by doctrinal and cultural shortfalls during the Pacific conflict.)

Felton, Mark. “Suicide Commandos”. September 28, 2015.

Gdula, Todd. “Real Steel: The Tetsubo”. December 2, 2010.

Komiya, Nick. “The Evolution of the Japanese Army Steel Helmet (1918-1945)”. October 23, 2015.

Komiya, Nick. “The Chrysanthemum and the Helmet”. November 22, 2015.

http://www.warrelics.eu/forum/japanese-militaria/chrysanthemum-helmet-597189/

Komiya, Nick. “Part One- The Development Story of the Type 90 Helmet”. November 15, 2011.

http://www.wehrmacht-awards.com/forums/showthread.php?t=554573

Komiya, Nick. “Part Two- Manufacturing and Issuing of the Type 90 Helmet”. November 15, 2011.

http://www.wehrmacht-awards.com/forums/showthread.php?t=554578

Tactical and Technical Trends was published by the U.S. Military Intelligence Service in World War Two from June 1941-June 1945.