(I wrote this article for the Japanese military collector journal, “Banzai”. I recently updated it and have posted it to FOWM.)

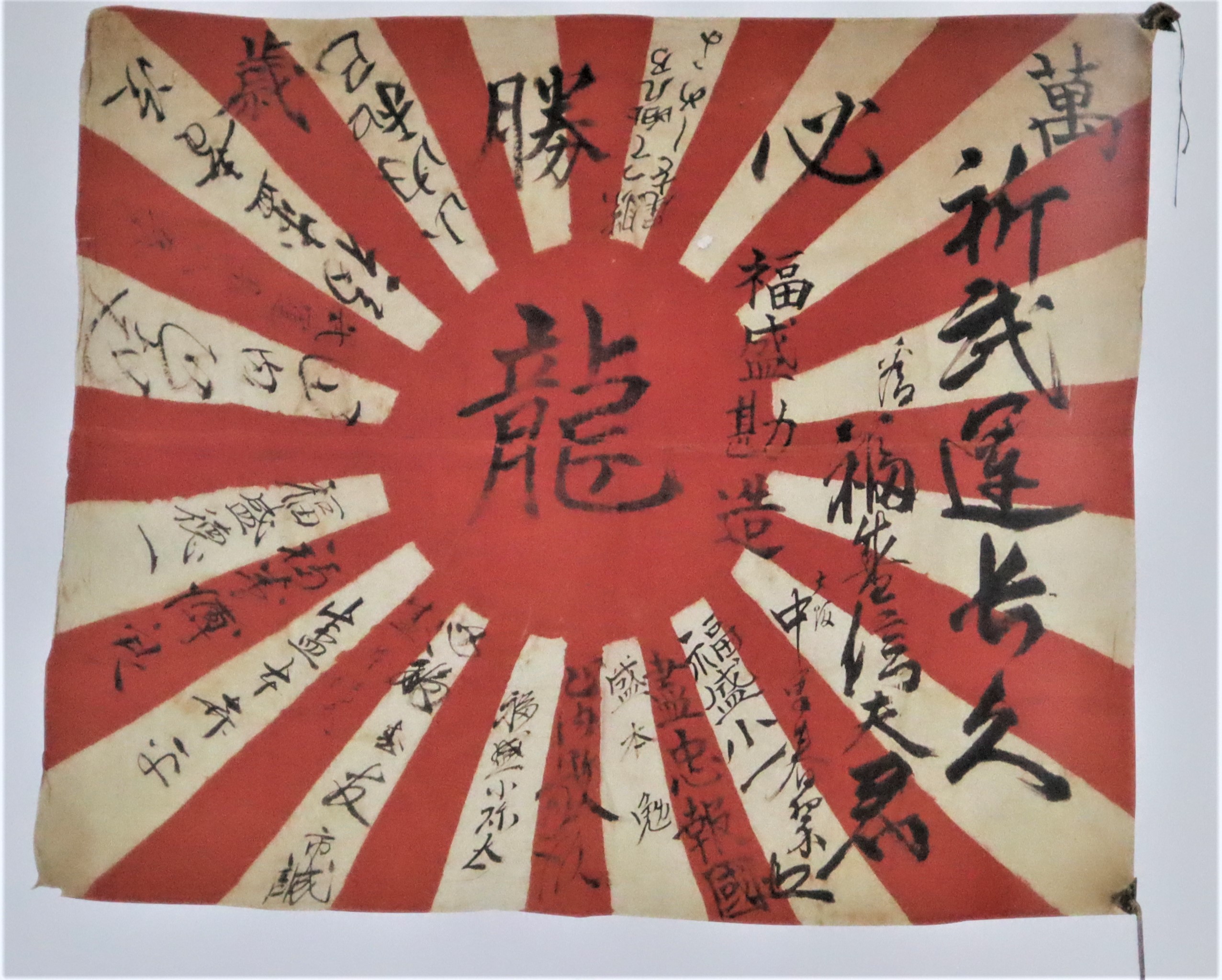

Nearly every collector or dealer of World War Two era Imperial Japanese militaria is familiar with the good luck signed national flag (hinomaru yosegaki). Along with the samurai sword, the profusely decorated Japanese character flag was one of the most iconic “bring-back” items from the war in the Pacific. To emphasize: the desire was so great to capture and bring home one of these flags from the field of battle, that a cottage industry sprang up among enterprising United States servicemen, to make fake examples and then sell them as real in order to fill the demand.

Thousands of vintage ones were undoubtedly carried by the Japanese into battle and very large numbers were eventually captured and brought home by the souvenir hounds of the Allied forces they faced off against.

As modern interest in Japanese military antiques has grown, so has appreciation for good luck flags. Until fairly recently, collectors of “real” military antiques, i.e. swords, arms, headgear, etc. have limited their acquisition, study and display of signed flags in any quantity for a variety of reasons: located near the top of that list is finding enough wall space in order to showcase a collection of Japanese character flags. Another more basic issue has been the difficulty by many to study and accurately translate the black inked characters encountered on the painted banner before them; not everyone has the ability to read the many pre-occupation period characters applied to the front of the flag. Complicating matters is the fact that there have been numerous changes to the Japanese writing system since war’s end that sometimes make it tough, even for modern Japanese speakers to fully read or interpret the World War Two era ideograms. This inability to easily convert into English the Japanese system of characters (hiragana, katakana, kanji and their various forms of script), has led some to repeat the sometimes false story that the only information depicted on the good luck flag are the historically useless signatures of long deceased and untraceable wartime well-wishers. But is this always a true statement? Let us take a close look at one flag’s translation and see what a careful study might reveal to the researcher…….

The standard hinomaru yosegaki was generally a presentation piece, given to the departing soldier, sailor or airman by his friends, family or co-workers as a gift. In some instances, the black painted characters emblazoned across the national hata or flag, do record nothing more than the names of friends. Other flag examples, however, might have additional information. For example, they may contain captions such as patriotic slogans of encouragement or song lyrics, placed next to a name. Even fewer examples have artwork painted or drawn upon the front. At times, a flag may be stamped with a shrine or temple seal(s), typically applied in red ink, onto the fabric. Some military personnel had their flags stamped at holy sites prior to departure; this could provide the name of the town from where the man hailed. Unfortunately, the name of the temple/shrine may not be unique and at times provides an incomplete lead, although not always. Some flags are infrequently stamped with a personal name seal. Along with other clues, these could help in narrowing down a flag’s former owner. Depending upon the person’s thoughts or inspiration, there might also be the lyrics from poems or passages from popular songs noted next to a signature. Oftentimes, in well studied examples, this added information may be used to ascertain the approximate time frame in which the flag was presented or it might indicate the town/city of the flag’s owner. The right flag may contain a whole host of exciting personal or general history of the time period from which it was taken. For those willing to have their flag translated, there is often the opportunity to mine a real kernel of historic interest.

For those collectors, hopeful of returning a flag like that to a family member in Japan take note: the attempt is often a difficult task. Some organizations have appeared over the years offering to return flags to family members in Japan. While there are successes and some flags have been reunited with the families of former Japanese service members, the numbers seem to be quite small. In the past, a 25 percent success rate in matching a flag to a family was considered normal, while others maintain that even this number is ambitious. In some instances where items are sent back to Japan and a family cannot be located, the piece might end up in a variety of places: perhaps donated to a temple or shrine, given to a museum, or stored in a box within an office with others. No matter what an owner chooses to do with it, these valuable bring back items from war are important historic relics from our past that deserve to be preserved. Often, the collector is the only one fulfilling that important task.

The flag offered here for observation and study is one of those remarkable pieces that has the power to open a window into the lives of the people who made history during what the Japanese call, The Great East Asian War. At the time of the conflict, regulations were in place that admonished anyone from recording information on the front of the flag that could be detrimental to the war effort. In reality, this rule was ignored often enough that flags and other items are often encountered today with fascinating and valuable content. It is important to remember too that not every flag was carried overseas. Some remained at home in Japan and were stored away until now. Historic objectivity is important, however, so please keep in mind that some of the text noted here, written during a different time more than 70 years ago, could be seen thru today’s lens as racist, or scandalous.

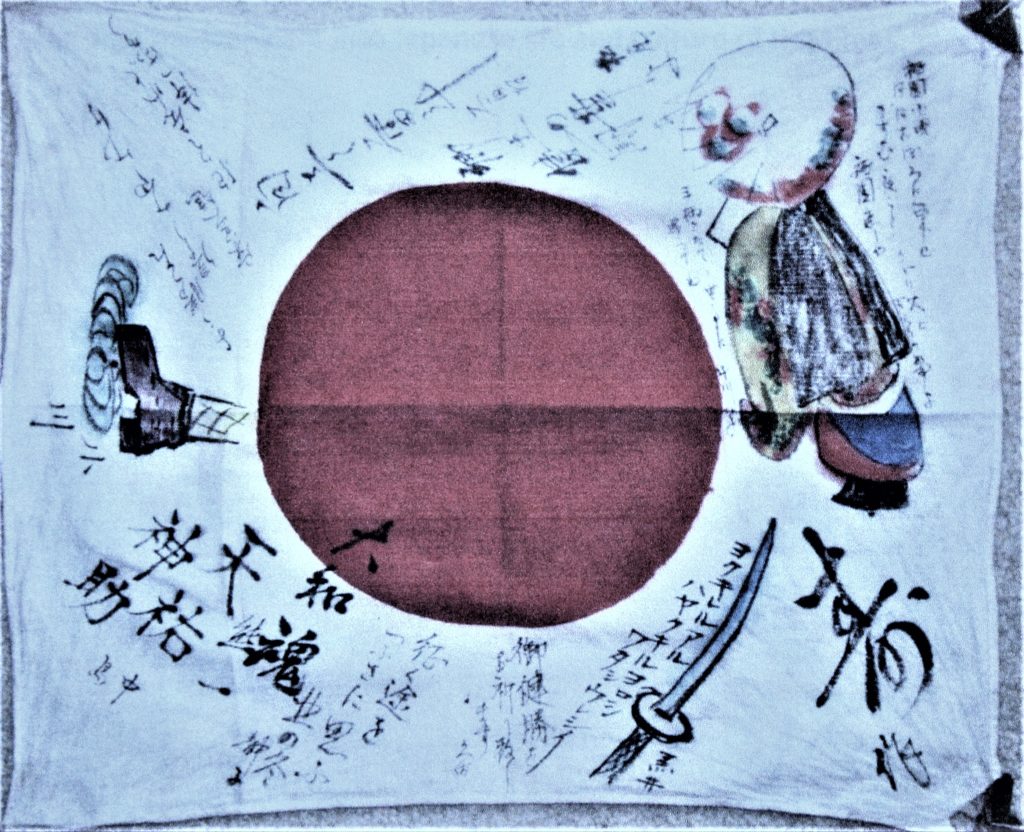

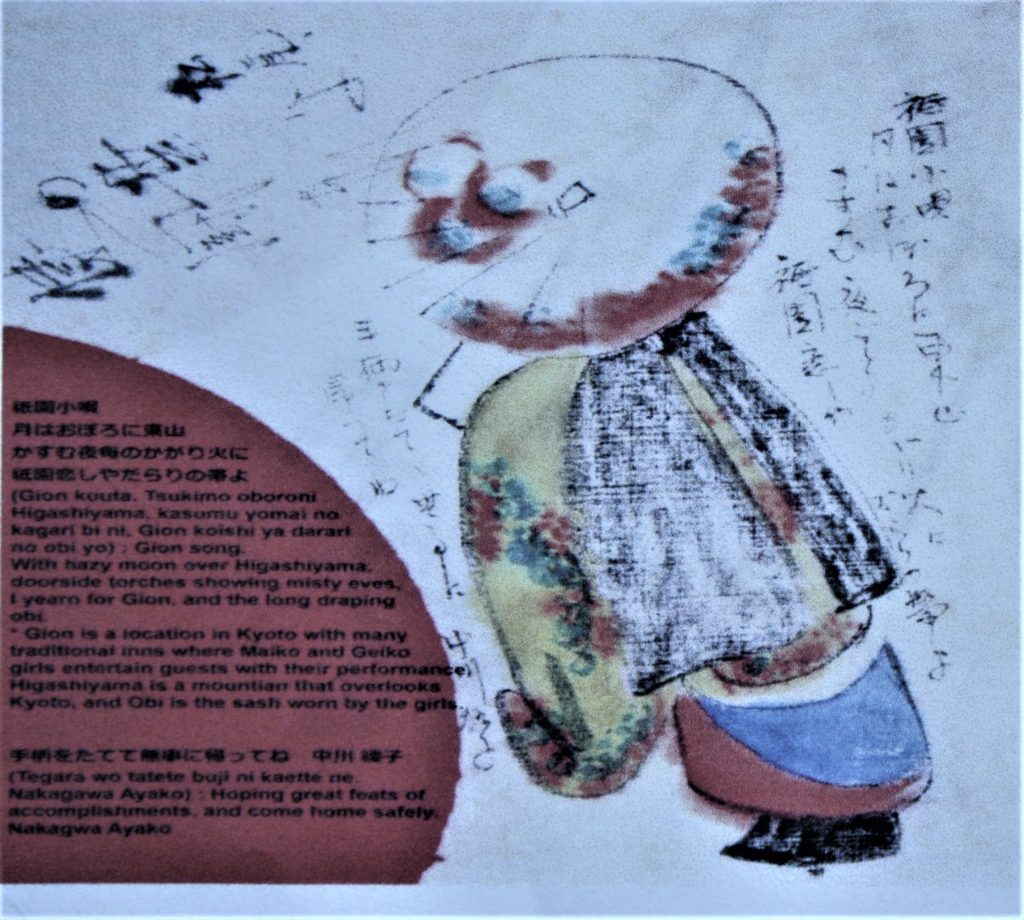

This beautiful and interesting good luck flag measures a small-ish 12.75 inches high X 15.75 inches long and is made from a cotton material. Brown paper re-enforcing tabs are present in both the upper and lower right-hand corners. Cotton tie strings are affixed to both tabs; the strings enable the flag to be tied to a small pole, a rifle sling/bayonet or virtually anything else for display should the owner desire. The flag is in overall excellent condition with no holes, tears or heavy stains present (see images). The upper right-hand quadrant displays a colorfully painted image of a Japanese maiko girl, holding her parasol. The images measures approximately 8.00 inches high X 4.00 inches long.

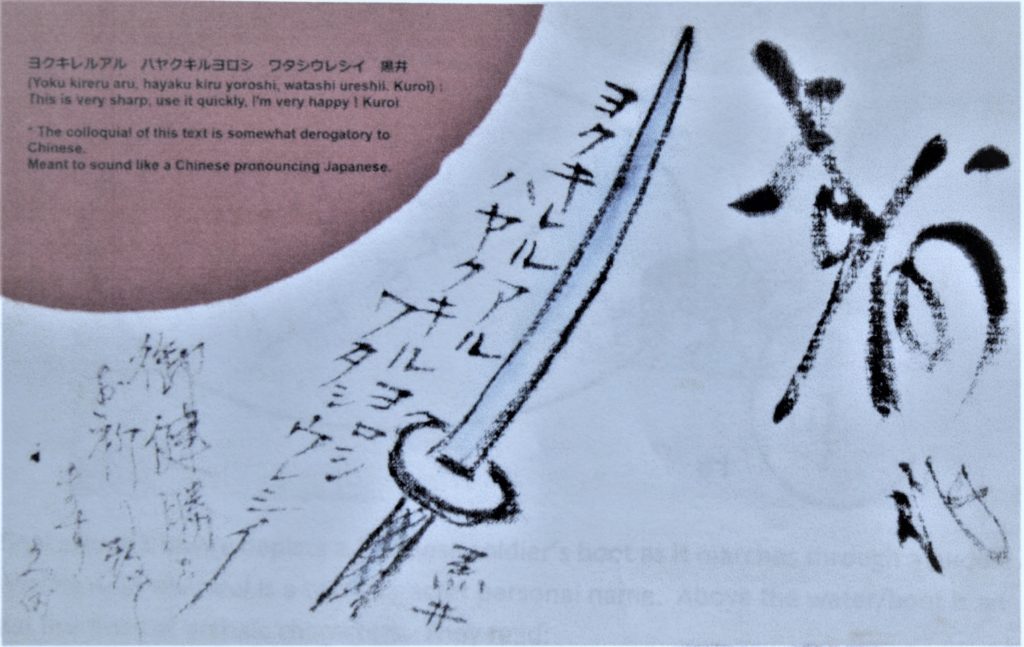

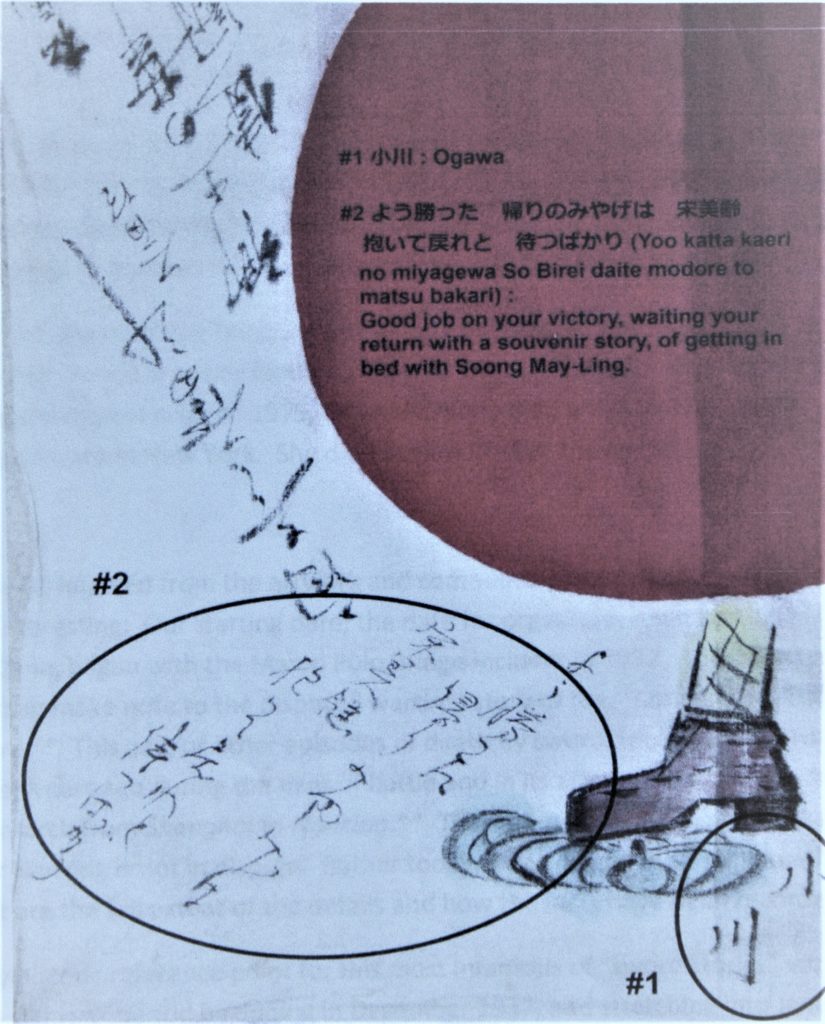

In the lower right-hand quadrant is a colorful rendition of a samurai sword that measures approximately 5.00 inches long. Near the nine o’clock position is a caricature-style drawing of a soldier’s boot, marching through a puddle of water. That image measures approximately 3.00 inches high X 2.75 inches long. It is conjecture whether this hinomaru yosegaki was carried by its owner into conflict or whether it was given as a presentation piece only. Based upon condition and the amount of colorful artwork scattered about the field, I would assume that this flag was kept secure, safely tucked away from harm.

As previously noted: many within the Japanese military may have received more than one good luck flag and large numbers of them were left behind at home. Coupled with this, not every flag came from someone killed in battle. The book, Imperial Japanese Good Luck Flags and One-Thousand Stitch Belts, written in 2008 by Michael A. Bortner, shows a series of photographs of Chinese and American troops taking good luck flags from the packs of Japanese soldier-prisoners during processing in the China-Burma-India Theater. On pages 120-121, PFC Harold Eifling of Michigan holds up his war trophy, taken from one such POW. Today, many of these various flags, including the ones sold online and at flea markets by the Japanese to collectors worldwide, make up the private collections of and are studied by historians, textile artists, art historians and museums around the world.

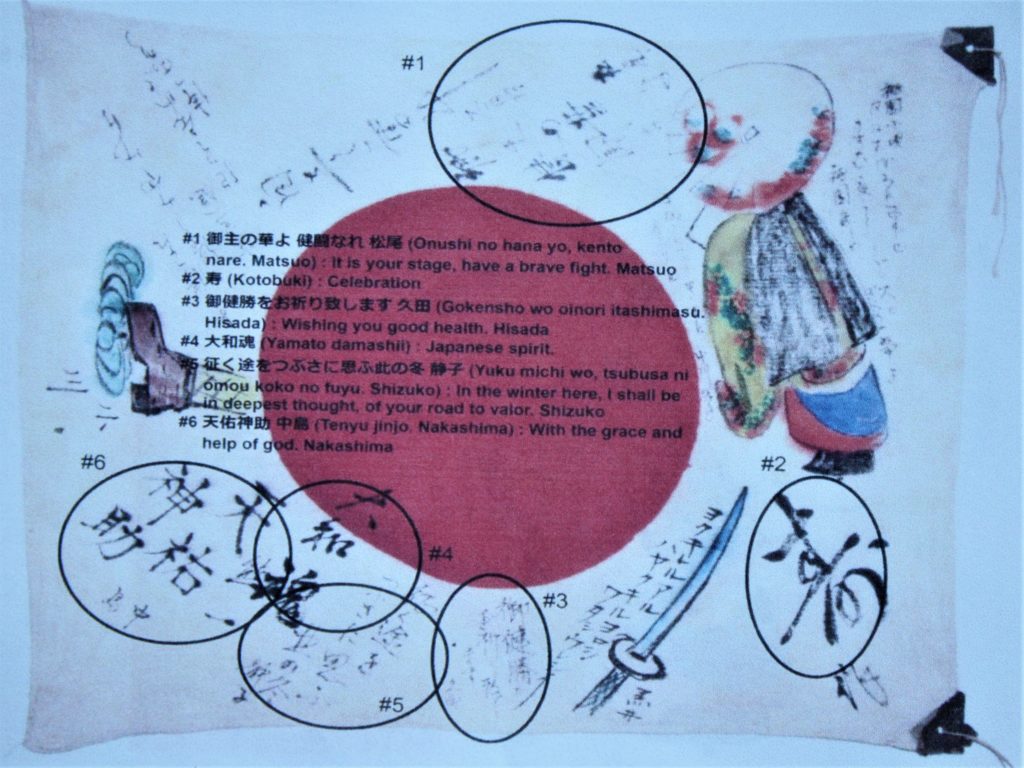

The photographs shown below contain blocks of translated characters. For ease, numbers have been placed next to most of the circled items that correspond to the matching English translation. Some of the ideograms represent names, patriotic sayings or slogans. Portions of the translation offer significant insight into Japanese life and culture of the times.

#1 “It is your stage, have a brave fight, Matsuo.” (The phrase written on the flag was by a friend of the owner named, Matsuo.)

#2 “Celebration!” (This is a wish to the flag’s owner, heading into the service or battle.)

#3 “Wishing you good health, Hisada.” (The phrase was placed upon the flag by a friend of the owner, Hisada.)

#4 “Japanese Spirit!” (This popular wartime slogan represented the spirit of divine duty, of unconquerable Japan. It has its roots in samurai legend and bushido, where the Japanese people were expected to fight desperately with courage and fearlessness, even in the face of death. Japanese fighting spirit was encountered by American servicemen throughout the entire Pacific; when in the face of terrific odds, many Japanese military personnel would refuse to surrender.)

#5 “In the winter here, I shall be in deepest thought, of your road to valor, Shizuko. (The sentiment and flag have been contributed by a female friend of the owner, Shizuko.)

#6 “With the grace and help of god, Nakashima.” (The sentiment was placed on the flag by a friend of the owner, Nakashima.)

The lines of characters to the left and right of the maiko make up a portion of what is called, “The Gion Song.” In addition, a sentiment and a signature have been placed nearby. The lyric reads:

#1 “With hazy moon over Higashiyama, door-side torches glowing in the misty eaves, I yearn for Gion, and the long draping obi.”

(Higashiyama is the name of one of 3 mountain ranges that rise above the city of Kyoto. It was also the name of a Japanese Emperor who ruled from 1675-1710. Kyoto is located in the central part of Honshu, Japan and was at one time, the Imperial capital of the country. Following the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the capital city was moved to Tokyo. Near the end of World War Two, the Allies placed Kyoto on a list to be considered for atomic bombing. It was eventually removed and Nagasaki took its place. Gion is a district within the city of Kyoto that contains many traditional inns and tea houses where maiko and geiko girls entertain guests with their classical songs and dance. In Kyoto, the word “geisha” is not used, rather there are two terms: maiko and geiko. The maiko is a Kyoto “geisha” in training, while the geiko is more experienced and in higher demand. Finally, an obi is a sash worn around the waist of the girl’s traditional dress or kimono. There are about 10 ways to tie an obi, and different knots are designated to be used during different events and on different kimono.)

#2 “Hoping great feats and accomplishments. Come home safely! Nakagawa Ayako.” (A sentiment and the signature of a female well-wisher have been added as well.)

The characters located alongside the samurai sword are written in order to be pronounced in the manner of a racial slang. In other words, they are meant to be derogatorily read as if a Chinese person is saying the Japanese words. Considering the fate of numbers of Chinese “collaborators” and “criminals” that fell into Japanese hands, the slogan while meant to be funny to those associated with the flag, is chilling. It reads:

#1 “This (the sword) is very sharp, use it quickly. I’m very happy! Kuroi.”

The final image depicts a Japanese soldier’s boot as it marches through a puddle of water. Visible near the heel is a two character personal name, seemingly associated with the art. Above the water/boot is an additional five lines of archaic characters. They read:

#1 “Ogawa.” (This is the personal name of a well-wisher. Unfortunately, we cannot say whether this is the name of the person who painted the boot artwork.)

#2 “Good job on your victory! Waiting your return with a souvenir story of getting in bed with Soong Mei-Ling!”

(Soong Mei-Ling is better known in the United States as Madame Chiang Kai-Shek. Educated in the U.S. between 1907 and 1917, the beautiful Mei-Ling eventually moved back to China following graduation from Wellesley College. In 1927, she married Chiang Kai-Shek and became the wife of the eventual Generalissimo. In that same year, China was splintered by Civil War. To complicate matters, the Japanese government telegraphed it future intentions toward China, when it invaded and later set up its puppet government in Manchuria in 1932.)

In 1937, out of necessity, the warring Chinese factions agreed to a temporary truce in order to unite and turn back the Japanese military following that country’s aggressive action at the Marco Polo Bridge near Peking/Beijing. In 1945, the Japanese were defeated and the Chinese Civil War resumed in earnest, finally reaching an unofficial conclusion in 1949-1950.

Following the defeat of her husband’s army by the Chinese communists in 1949-1950, Madame Chiang moved with her family to Taiwan, where Nationalists carried on resistance to communist rule. In 1975, General Chiang died and Madame Chiang then moved to her family’s estate in New York. She died in New York at the age of 105.

Conclusion:

What may be inferred from the artwork and the comments placed upon the front of this flag are historically telling. Our starting dates, the dates for organized, open hostilities between Japan and China, began with the Marco Polo Bridge incident which lasted between July 7-July 9, 1937. The sword reference (image #4), may reference the disputed wartime story of the “Contest to kill a hundred people using a sword.” This most widely covered episode of deaths by sword, took place approximately 80-plus years ago when the Japanese army was on the march from Shanghai to Nanking. That thousands of civilians were killed during the fight that led up to the capture of Nanking and afterward is not in dispute, although the total number is hotly contested. Rather today, what Japanese and Chinese historians and others argue about are the full extent of the details and how the facts have been recorded. It is argued that many of the “civilians” killed, were in fact Chinese soldiers who had discarded their uniforms and sought to blend in among the local population. For the Japanese, the story was seen by some as a tale of courage since the 2 Japanese officers involved, were portrayed as doing battle against an enemy armed with guns, while they only had their swords to protect them.

In any case, the likely historic reference point for this most infamous of “sword stories” would seem to fall within the period that began on November 30, 1937 and lasted through December 13, 1937 (the timeframe leading up to and including the Battle of Nanking). Japanese newspapers of the time, in particular the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, covered the story of 2nd. Lieutenants “A” and “B” of the Katagiri Unit who were engaged in a contest to see who would be the first to cut down 100 as they battled their way toward Nanking. Kuroi’s “sword” admonishment (image #4), noted on the good luck flag, seems to date it somewhere within the timing of the Nanking Incident and more than likely to the months thereafter when the story was receiving heavy attention. Of course, it is probable that the actual dates exceed the immediate battle as the “contest-story” continued to be discussed in Japan for some time after the event.

Although the debate with regard to the “contest” is understandably charged with emotion, much has been recorded and continues to be written with regard to it. One of the two officers in question provided a post-war interview in which he admitted his role in the incident; the 2 soldiers were later executed by the Chinese after being tried as war criminals. Interestingly too, the Japanese courts more recently denied a petition by relatives of the families for damages that they claimed were caused to them by the war time newspaper(s) that carried the stories. The judge ruled that there was simply not enough information available to prove that the story was false.

In addition to the previous account, the “Soong Mei-Ling” comment (image #5-2), would seem to place the flag within the same late 1930’s period of time. Based upon the personal messages recorded across the front of the flag, I think it is a fairly safe bet to assume that this particular good luck flag dates from the immediate post-1937 period and probably falls somewhere between the 1938-early 1939 timeframe.

For the collector of hinomaru yosegaki, there is great visual satisfaction in owning one or multiple good luck flags. In addition, by carefully studying the content on each piece: whether that be names, slogans, seals, or art, the passionate historian, may be able to use these incredible time capsules to learn more about the people who made them and the soldiers who carried them into battle. Not every flag tells a story; many simply contain signatures with no ability to be traced back to anyone- all context having been lost. On the other hand, sometimes a flag will emerge that has the ability to speak volumes about specific people and events that made history many years ago.

Japanese as well as foreign journalists and historians have contributed volumes to the research on the subject of The Great East Asian War and the Japanese Co-Prosperity Sphere. For those interested in doing more reading, the web has a number of links that may be examined. For anyone who desires to do a deeper reading on the topic of good luck flags or “the contest”, I also recommend the books and articles listed below as a starting point.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Good_Luck_Flag g

https://secure.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/wiki/Contest_to_kill_100_people_using_a_sword

http://www.wellesley.edu/Polisci/wj/China/Nanjing/nanjing2.html

https://secure.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/wiki/Nanking_Massacre

Michael A. Bortner, Imperial Japanese Good Luck Flags and One-Thousand Stitch Belts, Schiffer Military Books, Atglen, PA, 2008. Also available at www.FortunesOfWarMilitaria.com

Katsuichi Honda (1999) [Main text from Nankin e no Michi (The Road to Nanjing), 1987.] Gibrey, Frank, ed., The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan’s National Shame, M.E. Sharpe.

“The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt amid Fabricated Illusions”, 1971-1975. Article by Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, printed in The Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 307-340.