Battle Carried examines the history and meaning of tiger imagery of good luck flags in Japanese culture. Why was this an important book for you to write?

Battle Carried was important for me to write because it took into consideration two primary subjects that I had been passionate about since childhood: Japanese good luck flags and the tiger. Growing up, I had a fascination for flags; I drew and colored them and hung them on my bedroom walls. The more colorful the banner, the more I wanted to learn about it. At the time, the young student in me enjoyed learning about the histories of the nations that each flag represented. Flags and military history go hand-in-hand. I often thought how those colorful pieces of cloth could inspire ordinary men to accomplish extraordinary acts of courage in battle.

My interest in tigers was a little more straightforward. As a youngster I thought about pursuing a career in veterinary medicine. My home was an animal menagerie. I was always bringing some kind of pet home, or nursing an injured animal back to health. Based on that interest, I spent quite a lot of time reading about different animals, visiting zoos, etc. The reality for me was that while many people think of the lion as the king of beasts, I was more captivated by the beauty of the orange and black striped tiger. I did not know it at the time, but Asian culture actually celebrates the tiger as the king of the beasts. Years later, when I first heard that there were good luck flags with tigers painted on them, I knew that I wanted to eventually study them. It ended up being a match made in heaven. Battle Carried was a long-awaited outgrowth following the 2008 release of my introductory volume on Japanese good luck flags.

What kind of research did you undertake to complete this book?

I was familiar with doing research in history and anthropology at both an undergraduate and graduate school level. I began my research for Battle Carried by reading whatever I could find on the evolution, migration patterns and demographics of the tiger in Asia. As a student of anthropology, I had also studied Asian religious and philosophical worldviews. I wanted to better understand how and why those relationships came to be encapsulated into the Japanese tiger art good luck flags. Later, I thought that perhaps there was a connection between the animal that I saw in rare wood block prints (ukiyo-e) and those that illustrated the flags. It was fascinating to observe that the styles and poses of tiger art painted on flags during the World War Two era, often appeared to be near exact copies of those created, sometimes a few hundred years earlier. That realization led me to research the early Chinese influences that so heavily affected later Japanese art.

What is the most surprising thing you’ve learned about Imperial Japanese Tiger Art in your research?

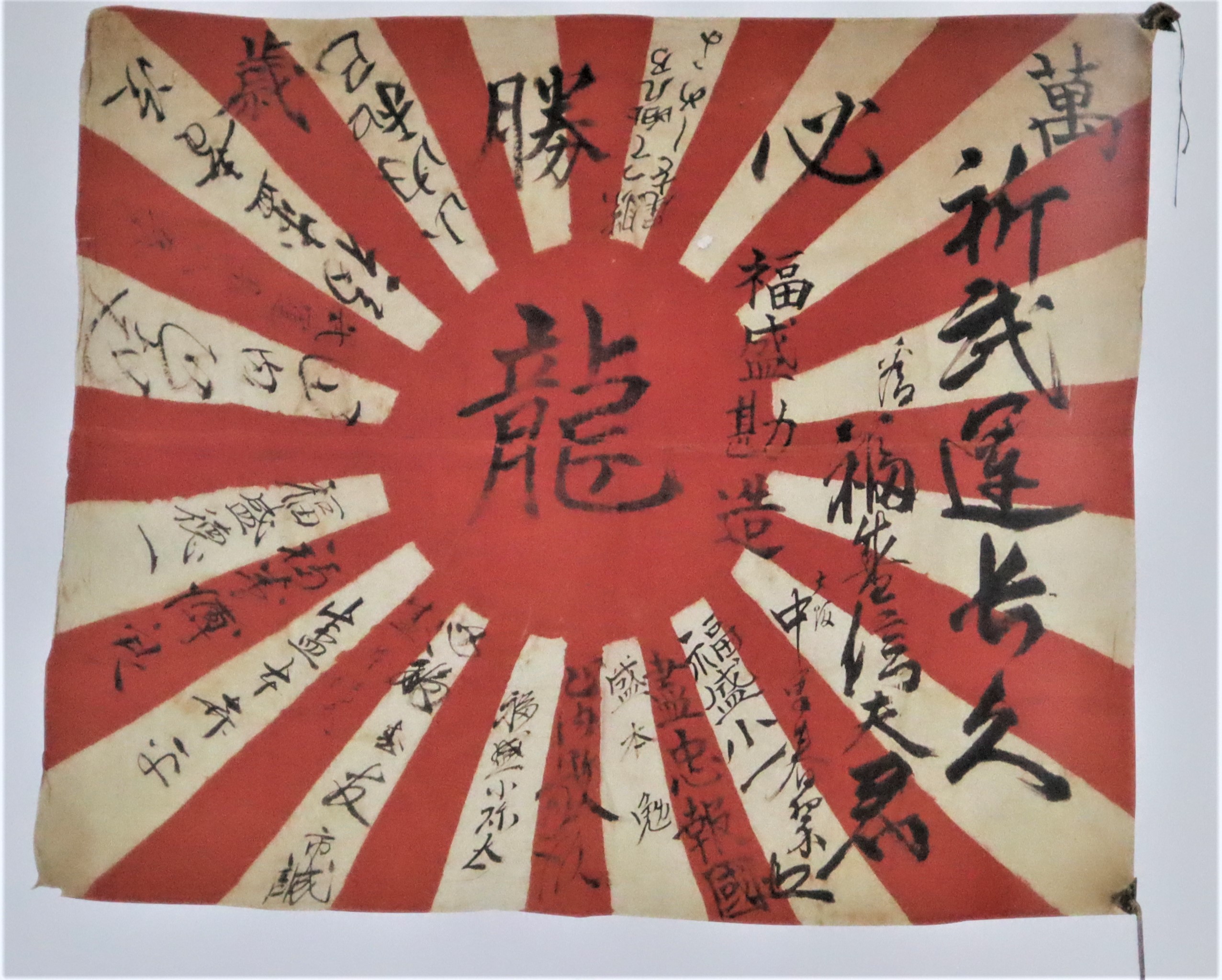

In Asian cosmology, the tiger was seen as a divine creature that played a significant role in how those cultures understood the origin, and evolution of the universe. In Taoist art, the tiger was frequently observed representing the “Yin” to the dragon’s “Yang”. When the tiger (tora) was complimented visually with the dragon (ryu), one of the most prolific pairings to illustrate the Japanese Zen Buddhist struggle for enlightenment emerged. With some exceptions, the Japanese embraced the zodiac system of the Chinese. The Tao constructs the world around two forces; They operate within a Yin-Yang relationship. Yin characteristics are composed of water, wind, earth, and are murky in nature. Furthermore, their essence is female, and static. The aspects of Yang incorporate fire, rain, the heavens, and brightness. Their essence is male, and energetic. The elements described may be manifested in the combined Yin-tiger, and the Yang-dragon; the pairing is known to the Japanese as uchu no tora, or “tiger in rain”. Zen Buddhism acknowledges an interplay between these two natures, one that exists throughout the entire universe. The tiger, with its courageous character, is accepted throughout Asia as the most esteemed of all the large wild animals. In pictures it is frequently positioned focused, ready to pounce upon its prey. Similarly, it is often portrayed descending along rocky outcropping, its belly stretched out low, hugging the ground. As a common theme, wind-strained bamboo thickets typically occupy the same image as the growling orange, and black striped beast. The late orientalist, Robert van Gulik wrote that, “In Japan, the tiger portrayed among bamboo stalks in the wind is known as take ni tora, ‘tiger in bamboo’. This representation is generally taken to symbolize that even the most powerful of terrestrial forces, namely the king of all animals, had to yield to the forces of nature. As such, the tiger in the take ni tora representation is also said to be identified with the wind itself, symbolizing as it were, the rustling wind in the bamboo grove.” The English born barrister, and art collector, Marcus Bourne Huish expounded upon this relationship further when he wrote in his 1889 book, Japan and Its Art that the tiger, “…is very often depicted in a storm cowering beneath bamboos, signifying the insignificant power of the mightiest of beasts as compared to that of the elements.” The powerful cat has a tempered force that is evident in its rigid muscles; allowing it comfort in its Yin/earth realm.

The dragon typically shows its force in a more spirited manner. He is often portrayed, surrounded within the heavens by angry rain clouds, and storm energized waters. Projecting himself out of the heavens, the dragon is frequently shown descending toward the earth where his Yang menaces, but does not dominate, the tiger’s Yin. Those two forces, uniformly matched are in balance, as they typify the universe’s harmonious nature.

In writing Battle Carried, I realized that the Yin-Yang relationship is one that all mankind would do better to more fully understand. When we strive to live in balance with the natural environment, the world tends to operate in a more harmonious fashion. Whenever mankind seeks to dominate or control that natural world, harmony is lost and systems break down. In Asian philosophy, the tiger as the king of beasts realizes that fact of life. Hopefully we will use that example to better steer our own destinies as humans.

I loved all the art you used in the book. What is your favorite art piece from this book?

My favorite piece of art is the 1885 woodcut triptych by the artist Koyama Chikusai titled Kato Kiyomasa on the Korean Campaign (p.33). The exploits of the samurai warrior Kato Kiyomasa were legendary among his friends and foe. He was famous, not only for his prowess on the field of battle, but also for his one-on-one fights against the fierce tiger. His fame grew to such an extent that other samurai attempted to elevate their own status by performing similar acts. Apparently enough samurai were being killed by their tiger opponents, that the Japanese leader, Toyotomi Hideyoshi banned his officers from taking part in the “sport”!

No other animal served to inspire and motivate the Japanese warrior in World War Two more than the magnificent tiger.

From the author of “Imperial Japanese Good Luck Flags and One-Thousand Stitch Belts,” Michael Bortner’s long awaited “Battle Carried” examines World War Two era Imperial Japanese good luck signed flags, featuring artistic renderings of the tiger.

“Battle Carried” examines the history, meaning and cultural context of tiger imagery as it applied to the decoration of good luck flags. Through hundreds of extensive color images and detailed close-ups, as well as woodblock prints and rare vintage photographs, this book superbly illustrates some of the rarest and most highly sought after specimens of tiger art flags, many of which are identified to their soldier, sailor and airmen owners.

“Battle Carried” is an invaluable resource for artists and scholars of Japanese culture, as well as for historians and collectors of flags and Japanese wartime memorabilia.